Below is an excerpt from the new book The Sopranos Sessions, written by Matt Zoller Seitz and Alan Sepinwall. To order your copy of the book, click here.

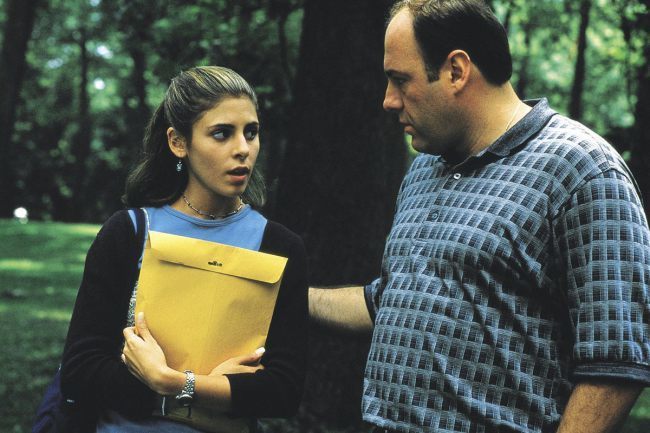

The pilot of "The Sopranos" built a world that was fresh and convincing enough to get viewers’ attention, and the next three chapters were strong enough to hold it. But it wasn’t until “College” that "The Sopranos" truly became "The Sopranos"—doing it, ironically, by separating three main characters, Tony, Meadow, and Carmela, from their carefully established community.

The audacity of the episode’s structure is itself notable: it concentrates on just two narratives, sidelining everyone else (except for Christopher, in a performance that’s literally phoned in). One plotline follows Tony as he tours universities in Maine with his daughter and spots Febby Petrulio (Tony Ray Rossi), a Mob informant whose testimony jailed several of his colleagues and might have hastened his own father’s demise. Tony’s obsession with killing the rat erupts on the heels of Meadow grilling him about whether he’s in the Mafia. His attempts to track and kill Febby with long-distance help from Chris are a source of farcical humor, with Tony taking an increasingly annoyed Meadow on a chase down a winding two-lane road, pawning her off on a group of local students in a bar, and constantly fabricating reasons for ducking into a phone booth.

The second story finds Carmela welcoming Father Phil Intintola (Paul Schulze), a celibate flirt, into her empty house on the same stormy night she learns that Dr. Melfi’s first name is Jennifer; distraught, she grumbles that Tony’s refusal to volunteer Melfi’s gender must mean he’s sleeping with her. A dangerous dance ensues. (Their chosen film is The Remains of the Day, a 1993 drama about a housekeeper and butler who are too repressed and bound by their obligations ever to be together—sound familiar?) The connections between the plotlines emerge organically via juxtaposition, without excessive prompting. Whenever “College” seems to hand themes directly to the viewer, it does so in such a plain-spoken way that they open new avenues of interpretation rather than close off existing ones. Meadow and Tony’s discussions about honesty, Carmela and Father Phil’s conversations about sin, guilt, and spirituality, and the scenes where both pairs ponder confidentiality and secrecy, refract off each other and illuminate the entire episode, and the series as a whole. “College” also gives us a clear sense of Tony’s strengths as a father—he can be a good listener when he takes off the tough-guy mask—as well as the better qualities that Meadow might’ve absorbed from Carmela: her ability to recognize others’ peace offerings (when Tony half-admits that he’s in the Mob, she admits that she did speed to get through finals) and her willingness to call bullshit on men she catches lying or evading. (“You know, there was a time when the Italian people didn’t have a lot of options,” Tony weasels. “You mean like Mario Cuomo?” Meadow counters.)

But all this is a mere sideshow to the hour’s bloody piece de resistance, Tony’s murder of the informant. It puts the Analyze This comparisons to bed forever, makes it clear that this isn’t some cute series about a henpecked Mob boss with troublemaking kids (“Wiseguys: They’re just like us!”), and announces that the evolutionary changes in TV storytelling that Hill Street Blues launched are about to be overthrown.

They attended SUNY Purchase together, and had acted together many times on stage and screen (and would continue to do so for years after The Sopranos ended, as toxic lovers on Showtime’s Nurse Jackie). There’s a shorthand and chemistry between them beyond the nearly romantic that’s enormously valuable for a story that has to push their relationship to its outer edges at a point in the series when we barely know either character.

This might seem an excessive claim to anyone who grew up on television after The Sopranos and watched countless protagonists do horrible things, sometimes defensibly, sometimes not. But back in 1999, the effect of this particular killing was seismic. Four episodes in, viewers had seen murder and violent death attributable to negligence or incompetence, but Tony didn’t commit any of the acts, nor was he directly responsible for their occurrence. Though he was way too free with his fists, Tony was a de-escalator: burning down Artie’s restaurant so Junior couldn’t have somebody whacked there, engineering Junior’s ascent to the top slot to head off a war, and so on. And although it seemed unthinkable that he’d go through the series without ordering at least one person’s death—he’d toyed with the idea—a killing like this seemed equally unthinkable, because TV protagonists didn’t get down in the muck like that. That was what henchmen and guest stars were for.

Let’s back up from the murder and examine its dramatic architecture to determine what made it so unusual. It’s not the choice of target. Febby may have left the life years earlier, but he hasn’t really reformed. Deep down he’s still a criminal, and he’ll always be a rat, and because we’ve spent lots of time with Tony and none with Febby, and accept that this is the kind of thing mobsters have to do because of their code, of course we’re going to take Tony’s side. Also significant: this is a crime of opportunity. Tony didn’t drag Meadow to Maine just to track down Febby and kill him, which would’ve been reckless and deranged versus merely impulsive. He isn’t killing some random person for disrespecting him or to cover up some other offense. This is a former gangster—and a poor excuse for one. He sold out his friends (one of whom died in prison), then entered witness protection until the FBI ejected him. Now he’s been living under an Anglicized alias, Fred Peters, and lecturing about his former life to college kids. We already know (from the pilot and “46 Long”) Tony and the others consider this sort of behavior a whackable offense.

All of this places Febby squarely in the category of “work problems.” To frame things in terms of the Godfather films, as "The Sopranos" often does, Febby isn’t that anonymous sex worker in "The Godfather Part II" who the Corleones killed to indebt a senator; he’s more akin to Frankie Five Angels, the underboss in II who becomes a state witness and kills himself after committing perjury. The Corleones became American folk heroes despite being thieving, racketeering monsters because, with few exceptions, they only killed other mobsters and their collaborators, and only ones that were coded as worse than the Corleones.

That’s the case here as well, though we feel for Febby’s wife and daughter even if we don’t care what happens to Febby. No, Febby’s murder was startling because of the context—a father-daughter road trip, mirroring Febby’s life with the wife he’ll never sleep next to again and the daughter he won’t see grow up—and because of the joy Tony takes in doing the deed. There’s no regret or distaste on his face as he twists those cords, only glee. The most frightening thing about Tony is the way he seems to trade depression for euphoria when hurting people. James Gandolfini’s face splits into a predatory grin, practically a leer, and he throws his tall, broad frame into the action with the furious precision of a smaller, more graceful man. His arms and fists are a blur, his eyes blaze, and flecks of spittle fly out of his mouth as he curses the men he’s battering and tormenting. He’s never been scarier.

The lead-up to the strangulation reveals the scene’s primordial essence: we’re watching an apex predator stalk and kill its prey. We got a taste of this approach earlier in the episode when Tony visited Febby’s home and watched him tell his daughter good night while sitting in a hot tub with his wife. Right before Tony sneaks up behind Febby in the woods, Febby hears a noise in nearby brush and looks to see what caused it, and we get a cutaway shot of a deer gazing at him, its curious face framed by the greenery.

The sequence of actions that brought us to this point represents a journey backward in time: Tony and Febby arrive by car, a twentieth-century form of transportation; Febby loses his revolver, a nineteenth-century weapon, during the struggle, and there’s a shot of the piece dropping onto the earth beneath his feet; then Tony strangles him and strangles him and keeps strangling him, an act of Shakespearean viciousness. The scene lasts much longer than you expect, until the audience feels assaulted as well. The editing cuts between tight close-ups of Febby’s face, Tony’s hands pulling the cords tight around Febby’s neck, and Tony’s face contorted in euphoric rage, his front teeth framed by his snarling mouth (like an upside-down smile) so that they evoke a carnivore’s bared fangs. Close-ups of Tony’s hands reveal that he’s choking Febby so hard that the cords are cutting his skin. After he drops Febby’s lifeless body, he stands up and walks past the travel agency as insects whir and birds caw. He looks up to see a flock of birds—ducks, probably—in a V formation, a shot that resonates in multiple ways, none of them reassuring.

Shots of birds in flight after a character’s death always evoke a soul departing. In this case, they also amplify the sense that we’ve just seen prehistoric savagery occur. These ducks harken back to the ones that left Tony’s swimming pool, part of a narrative that we associate with Tony and Livia’s relationship: her hold over his imagination, the genes that encoded half of the beast in him. And they stand in for the safe family and feelings of peace that seem to remain forever beyond his grasp.

Carmela’s story is nearly as unsettling, partly because of how it fuses with Tony’s. Tony’s half of “College” is a scaled-down, two-character exploration of what it means to be Tony Soprano, a theoretically respectable man with a house, a wife, a kids, and a secret criminal life; Carmela’s half is about being his complicit partner. We get a sense of how repressed she is, thanks to her acceptance of the contradictory sexual values of Mob marriages (men are expected, even encouraged to take mistresses; wives are supposed to be faithful) as well as the sexual politics of Roman Catholicism. Two of the movies that are name-checked in this episode, The Remains of the Day and Casablanca, revolve around great loves that cannot be. It’s spot-on that she’d bond with Father Phil over these sorts of movies, and that she’d select a priest as the vessel into which to pour the specific desires, fears, and affinities that Tony would never entertain. There’s (almost) no danger that the frisson of attraction will become physical.

Nevertheless, her evening with Father Phil unfolds like a date from the start—she even takes a pass at her hair before letting him in. Their interactions show that they genuinely like each other, and that each is getting something out of the relationship. Carmela gives the priest-plus an outlet for his intellectual curiosity beyond matters of scripture, plus imaginative fuel for fantasies of a life where he could have a normal relationship with a woman (thus their discussion of Jesus coming down off the cross in Scorsese’s "The Last Temptation of Christ"). Father Phil gives Carmela a sympathetic ear, appreciation for her food and her personality, and a means to discuss religion, philosophy, and movies-as-art. The script is clear on what’s at stake for them: it’s never a good idea to court a gangster’s wife, or for a gangster’s wife to step out. But the fact that Father Phil is married to the church adds another layer of taboo. When he rushes to the bathroom to retch after moving in for a kiss, it’s not just the alcohol causing his body to rebel.(The moment connects with the "Last Temptation" discussion, as well as with Tony’s line while killing Febby: “You took an oath and you broke it!”)

It seems fitting that “College” puts Carmela’s confession to Father Phil and her subsequent taking of Communion—the moments when she’s most emotionally naked—at the midpoint, where these characters’ first sex scene might go were this a novel about two lovers. The close-ups of Father Phil pouring wine into a Communion cup and delivering it straight to Carmela’s lips along with the Host are the true consummation of a storyline about sexual energy being teased out and shut down (or redirected). It’s in these scenes that we move beyond the question of “Will they or won’t they?” and enter darker territory. Carmela is in denial about her husband’s affairs, but those pale in comparison to the other sins, the literal crimes, that she can’t bring herself to confront. Her confession to Father Phil, delivered on the same couch where her family watches TV, sums up this series’ fascination with evil and compromise, false faces and self-deception. “I have forsaken what is right for what is easy, allowing what I know is evil in my house,” she says. “Allowing my children—Oh my God, my sweet children!—to be a part of it, because I wanted things for them. I wanted a better life, good schools. I wanted this house. I wanted money in my hands, money to buy everything I ever wanted. I’m so ashamed! My husband, I think he has committed horrible acts. . . . I’ve said nothing, I’ve done nothing about it. I got a bad feeling it’s just a matter of time before God compensates me with outrage for my sins.”

Late in “College” there’s a scene with Tony that explicitly connects the two stories. As Tony sits in a university hallway at Bowdoin College waiting for Meadow to be interviewed, he looks up at a quote emblazoned on a large panel hanging over a doorway: “No man can wear one face to himself and another to the multitude without finally getting bewildered as to which may be true." It’s a slight misquote from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s "The Scarlet Letter," about a minister who falls in love with a woman and breaks his vows.

Excerpt from the new book The Sopranos Sessions by Matt Zoller Seitz and Alan Sepinwall published by Abrams Press; © 2019 Matt Zoller Seitz and Alan Sepinwall. To order your copy of the book, click here

Matt Zoller Seitz is the Editor at Large of RogerEbert.com, TV critic for New York Magazine and Vulture.com, and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in criticism.