Among other things, Brian Eno is a pioneer in what’s called “generative art.” His work in the field began when he was an art-rock star, playing in the band Roxy Music. While he made lots of skronky sounds on early synths with those fellas, his first instrument, as he says in this engaging documentary, was the reel-to-reel tape recorder. Futzing around with it, the ever-curious Eno came to understand you could do a lot more than just make recordings with it. He started ping-ponging the inputs and outputs of two side-by-side tape machines, which could create a long delay within the sound itself; these experiments formed the basis for his collaborations with guitarist Robert Fripp on the seminal 1973 album “No Pussyfooting.” Fripp dubbed these techniques “Frippertronics,” and he’s been using them — and their digital variations — ever since. But they’re only Frippertronics when Fripp is involved. Eno on his own used them to create Discreet Music, a pioneering work in what’s been called “Ambient” or even “New Age” music. Eno’s subsequent work in generative art extended into visuals as well, including a piece of software titled “77 Million Paintings,” which, over the course of time, will produce just that.

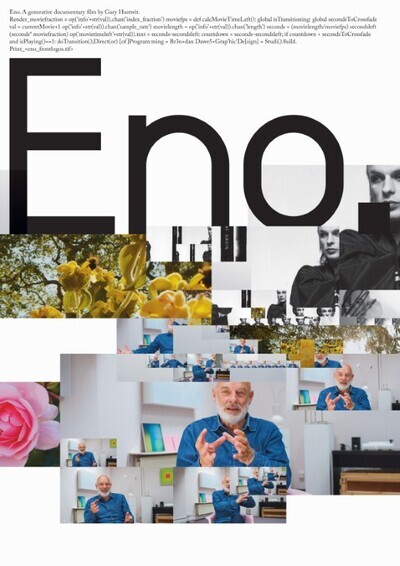

I bring all this up because Gary Hustwit, the director of this documentary, has used the potential of generative art to give this movie a gimmick, which some might argue isn’t needed. This movie’s DCP contains software that changes the movie every time it’s screened. While what you’ll get when you see it will invariably be a little over 90 minutes of Eno explaining his self, life, and career (collaborators including David Byrne and U2 are seen in archival footage, although Laurie Anderson shows up in newly-shot material, except she’s playing a role rather than contributing personal insight), it won’t be in the same order, and little bits will drop out while others will be added.

It is an intriguing idea, on the one hand. For a critic, it's a bit of a challenge on several fronts, including the one where you try to give a cogent summation of the scenes. As a viewer … I don’t know. I’m an Eno fan from way back when he was an androgynous noisemaker in the early ‘70s, and I’ve always been a little defensive about it; I remember being at a party with some kids a third my age who were discussing his earlier edgier work, and I just got my “you can’t tell me” back up. While still not quite a household name, except among crossword solvers, he’s a multi-platinum producer and such, and a guy always on a search; while he never uses the word workaholic, he allows that when he does stop working, he inevitably slumps into misery.

He's now white-bearded and definitively bald, and he’s even got a little paunch. (In the Roxy days, he looked like a strong breeze would blow him away or that he’d collapse under the padded shoulders of one of his elaborate stage costumes.) Although he still very much retains the cerebral aura derided by petulant punk partisans Tony Parsons and Julie Burchill in their 1978 slam book The Boy Looked at Johnny, he’s incredibly amiable, good-humored, and loose here, particularly when he calls up Little Richard and the doo-wop group the Silhouettes and sings along with them. He can be disarmingly frank; he admits that he made his 1975 masterpiece Another Green World in tears the whole time, completely unsure of what he should be doing. He also speaks of being hurt by the dismissive critical reaction — he uses the phrase “old rope” as a typical characterization — to some of his ambient work.

If the movie leaves you wanting more, that’s because, as we’ve established, there apparently is more. A colleague complained bitterly as we were walking out that he felt potentially deprived of the skinny on Eno’s collaboration with a certain artist … but I had to tell him he was mistaken in expecting it because, contrary to his impression, the artist had never been actually produced by Eno. Still, he was squirrelly and I kind of don’t blame him.

Nevertheless, the film works most of the time, largely because its subject is such interesting — and warm — company.

Glenn Kenny was the chief film critic of Premiere magazine for almost half of its existence. He has written for a host of other publications and resides in Brooklyn. Read his answers to our Movie Love Questionnaire here.

90 minutes