When James Redford showed up for our interview, I initially thought there must’ve been some sort of mistake. The man seated across the table from me looked so much like his father—the iconic star of “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,” “The Candidate,” “All the President’s Men” and “All Is Lost”—that I assumed Robert Redford had simply showed up in his son’s place. Yet this was indeed James, an accomplished filmmaker in his own right, not to mention a tremendously gracious and impassioned humanist. His latest documentary, “Resilience: The Biology of Stress and the Science of Hope,” has been selected as the opening night feature for the first-ever Chicago Independent Film Critics Circle Showcase, and quite frankly, the Windy City couldn’t be more in need of this film. It’s an engrossing study of how Adverse Childhood Experiences (or ACEs) can be linked to destructive behavior and medical diseases that are diagnosed later in life. Considering the overwhelming amount of stress 2016 has offered mankind, Redford and I had plenty to discuss.

In the conversation that follows, Redford speaks with RogerEbert.com about his approach to documentary filmmaking, his thoughts on Trump and how he managed to get swept up in the World Series hysteria.

“Resilience” reminded me of your father’s directorial debut, “Ordinary People,” in how it explores the catharsis one feels when opening up about traumatic events during therapy.

I never thought of that! In regards to therapy and psychiatry, sometimes you can’t see certain things yourself. You don’t have that perspective. Now that you’ve pointed this out, I can see that connection. That movie was made here in the North Shore, and it was made during my senior year in high school, so I would come out and visit the set. In every socioeconomic strata, there are particular sets of challenges when it comes to stress and repression. In affluent communities like the one in “Ordinary People,” there’s often the myth of invincibility and the myth of the happy life. How could these people possibly have anything to complain about? After all, they live in a beautiful home with a garage, a dog and a white picket fence. Yet that’s often a façade for what’s truly going on in people’s lives—abuse, neglect, mental illness and so many other things. That’s when your economic status can actually become a barrier to you getting help because it’s very easy to become cut off in a strange way. You may have the resources for therapy, but you’re not in an environment where it’s the norm to think of yourself as someone who is carrying around a lot of baggage.

Have your own past struggles with liver disease played a role in leading you to explore issues regarding health on film?

Yes, though it didn’t happen overnight. I started out studying literature and discovered that academics weren’t for me. Storytelling and screenwriting were much more intuitive and natural things for me, and my entry into the film business was through screenwriting. At the same time, I was dealing with a lot of health issues from childhood that caught up with me at 30. I went through the harrowing ordeal of two liver transplants, and I was screenwriting at the time. After I came through that experience, I felt an overwhelming sense of gratitude. It’s different from the feeling you get after you’re nearly hit by a car and find that you’re still alive. You might feel lucky, but that doesn’t generate gratitude. What generates gratitude is the vast network that saved my life—it was the donor family, the nurses, surgeons, doctors—it took an enormous group effort for it to happen. When you see what society can do, that changes you, and my first film, “The Kindness of Strangers,” focused on that. I’m at a point right now where I’m very interested in the nexus between documentary filmmaking as a form and creating tools for change, and in some ways, it’s a hybrid. There are some things in my films that you don’t normally see in other pictures, but they are a necessary component of our impact campaign, and we have to manage them. I’ve learned through hard-won experience that the more information you’re conveying, the more artful you have to be about the way you’re conveying it.

How did you go about making “Resilience” more artful?

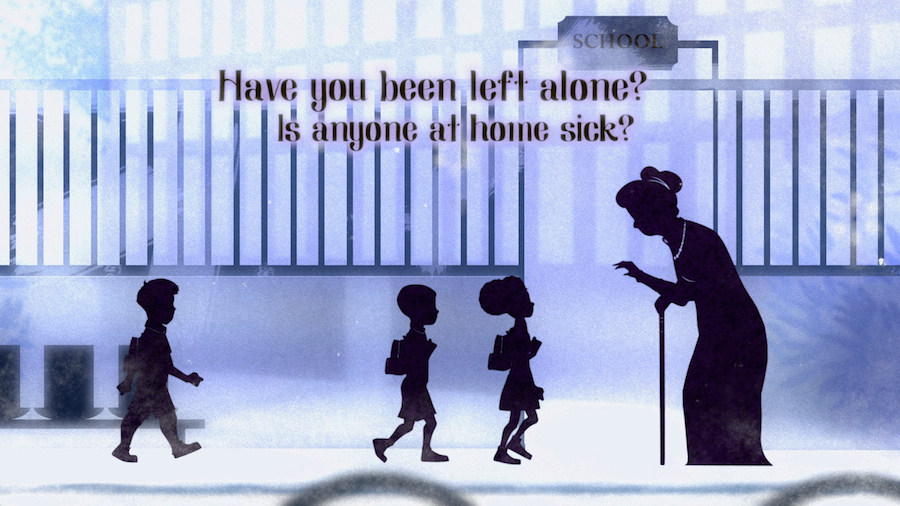

That was the challenge. Our project centering on topics of stress is a twofold initiative: one of them is “Paper Tigers,” and the other is “Resilience.” “Paper Tigers” came out the year prior, and that was a far more traditional vérité documentary. I spent a year observing trauma-informed education at a high school. “Resilience” was always seen more as the “proof in the pudding” companion film that goes deeper into the science of what’s going on and the rationale behind why it’s important. They are very different films in that regard because as you can see, “Resilience” doesn’t have a beginning, middle and end story arc. It’s sort of like an essay with chapters, and it’s an hour long because of that. We had an original score by Garth Stevenson, an up-coming artist who is very popular in the indie festival circuit. The animated sequences took a lot of time, and frankly, it was expensive, but it was important to make the information more digestible. To me, these are fun challenges to tackle. Some films can really spark significant shifts—you look back on a film like “Philadelphia” that became a watershed moment. It can definitely happen.

According to the Internet, November 2nd was National Stress Awareness Day, which was rather fitting, considering that it also happened to be the same day as the agonizing yet ultimately glorious World Series finale.

You know that feeling when you get bad news? That feeling that you get in your body? I’ve come to consider that a poison, and when that emerges, I go out of my way to deescalate it. I’ll step out of the room if I have to because it is literally toxic. I’m not even a Cubs fan, I don’t live here, and I initially thought that it would be great to watch a World Series game that I was utterly uninvested in. I watched it at the hotel bar and within five minutes, it was as if a contagion took over me and I got completely sucked in to the drama. When the Cubs were up 5-1, everyone was like, “No no no, this is not good. You have to understand: this is how it always goes. The other team will come roaring back,” and sure enough…

It felt like something out of a movie.

Exactly! That’s what I was thinking. I could see the structure—the storm was the end of Act 2.

Even worse is the stress generated by this year’s presidential campaign.

It’s sort of like that game last night where the polls are tightening as you get down to the last days. Yet when you go back and look at the very start, Trump has never truly overtaken Clinton. There may be some percentage polls that suggest otherwise, but if you look at Nate Silver or The New York Times forecasting, he’s never really been within striking distance. I don’t think there’s any example of someone who was behind the whole way and then suddenly caught up in the last hour. At least that’s what I’m telling myself. When I look at the brand name on the Trump Tower across from my hotel, it reminds me that while those of us who are media savvy can see all of his hypocrisies, the average person who walks by that building and gazes up at that brand name on that building will see it as invincible. It seems larger than life. Why would we want a brand name like that running the country? Just today in The Times, there was an article about Trump’s true net worth that illustrates how he’s made a habit of exaggerating everything. He’s even dishonest about the size of his buildings

Not to mention being dishonest about your own father. The back cover of Trump’s book, Crippled America, quotes your father saying, “I’m glad he’s in there, being the way he is,” while conveniently leaving out the rest of the quote: “He’s got such a big foot in his mouth, I’m not sure you could get it out.”

[laughs] I did not know that! To be honest, the main reason why we’re here in Chicago is Karen Pritzker. Both of our children are dyslexic, and I’ve learned that one in ten people walking on Earth have some degree of dyslexia. When we first met, our children had just come through the trial by fire of getting their education while dyslexic. Karen and my wife met at a party and they talked about their mutual desire for there to be a film that showed how dyslexia isn’t an academic death sentence. That became the first film Karen and I made together, “The Big Picture: Rethinking Dyslexia.” It was an HBO film and that was the start of our company, KPJR Films. We both felt that our film changed the public awareness and the core of that film was the emerging science around MRI brain scans. It put to rest the misconception that dyslexia is a “rich person’s word for being lazy.”

It was Karen who brought me the ACE study about toxic stress and said, “I think this is the next big thing in public health.” Four years later, I have to say she was right. When we started our research for “Paper Tigers” and “Resilience,” there was hardly a squeak about these studies online outside of professional circles and there were only three or four schools that were doing things differently. Now there are plenty of schools in the New York public school district that are trauma-informed. There’s been a demand for community screenings of both films way beyond what we would’ve predicted. I’d like to say it’s because I’m some brilliant filmmaker, but that’s not really true. What’s true is that Karen was right. By the time we were done, the issue was gathering steam and the film helped accelerate that. I call the Pritzker family the Chicago Medicis, because if you were to really look at how many good things are going on in philanthropy, the footprint of that family is huge.

I was greatly intrigued by The Legend of Miss Kendra, a program designed to get young kids to open up about trauma that is considered taboo in the classroom.

Probably the most explosive part of the film is the Miss Kendra segment because we still have a taboo about openly acknowledging sexual abuse. The prevailing thought is that kids are resilient—they play and they laugh and they run around, and it’s really when they get to be teens that their lives get more difficult. The truth is that just because kids seem to be having a good time doesn’t mean that’s what is really going on. The folks at the Post Traumatic Stress Center understand that a denial of trauma simply creates more isolation, and makes it much more difficult to offer a buffer amidst all of this adversity. Kids feels empowered when they are given some standards and some norms for themselves. How do you get kids from broken homes to understand what is okay and what isn’t at an age when that job usually falls to the parents? As is often the case, it falls to the schools, and that Miss Kendra program is mushrooming. They are in the middle of creating a reputable model of a toolkit that will be introduced with the assistance of trauma therapists in order to bring the program into more schools.

It’s so important to tackle an issue early on before it festers into an even greater problem.

You’re right. The animal part of us, as humans, is highly reactive. We are really good at responding to a crisis when the s—t hits the fan. But the part of us that is evolving towards something that is more than animal is the part of our brain that logically identifies how if we don’t fix a situation right now, it’s going to be ten times worse ten years from now. We have so much trouble investing the energy now to prevent something much worse from happening later. In some ways, that’s going to be our fighting challenge as a species because everywhere you look, that’s what’s being required of us right now, to be proactive. Not only does unmitigated toxic stress put kids at risk of health problems, it also makes it more likely for them to settle into destructive behavior. Crime and violence and homelessness and teen pregnancy and obesity—a lot of this is behaviorally related due to not dealing with stress. That’s why it is crucial to help families get off to the right start, because the farther back you go, the more profound the benefits of an intervention can be. In “Resilience,” we provide statistics detailing how the state of Washington benefited from implementing these programs. They had a coalition of philanthropists who put money in a state-wide effort, and the money basically paid for itself. Although it didn’t go back to them, the gift was twofold—it was a philanthropic gift that made it happen, and it saved the state a lot of money.

In many ways, Mary Tyler Moore’s character in “Ordinary People” is a tragic embodiment of repression in how she struggles to mask her wound rather than acknowledge it.

She’s a cautionary tale, and you’re left haunted by that character. I had the privilege of researching and bearing witness to people and programs that can help. I saw some remarkable recoveries, but at the same time, I couldn’t help thinking of all those missed opportunities. It doesn’t take as much as we think to make a big change. Empathy and compassion aren’t just words that liberals like to say, there is a scientific and medical basis for them. My hope is that these films will make people a little more curious about people’s histories, and inspire them to ask what’s going on rather than make quick judgments. If we make that shift, then good things will come from it.

I also loved how your film attempts to obliterate the notion that people are doomed to poor life outcomes because of where they’ve been raised.

One of the advantages of this science is that it transcends geographic, political and socioeconomic boundaries. I traveled with this film to Colombia last Spring and there you see it through the lens of generations of a war. How many young people there are dealing not only with trauma but with growing up in a world where violence is a way of life? We also screened both films in Kazakhstan, where there has been very little social service support for those who are marginalized. There are rewards for those that do well, but if you don’t, you are essentially nonexistent. I didn’t realize that these movies could be taken outside of the country and still resonate. I’ve encountered a lot of people who feel that anything that isn’t aggressively tackling the roots of race and poverty is just a distraction because so much emanates out from those problems. Any other Band-Aids are just a distraction to them. Of course, the war on poverty is vital and you need people involved who can lead sea changes, but the question is, what do we do in the meantime? By avoiding these options, you’re also increasing the likelihood that the voices of people who have experienced intergenerational poverty will be buried. If you can help them survive, then they will become the voices that solve the problems.

Tell me a bit about your next film focusing on renewable energy.

I have a film non-profit called The Redford Center and we’re ultimately aiming to support younger voices in making environmental documentaries. We just awarded six grants to young environmental filmmakers, and we are on the lookout for wild and weird voices who are trying to redefine what it means to work in the environmental space. Traditionally, there is a puritanical aspect to the environmental movement in general, and a lot of times films feel like they have to honor that in some way. I count myself as guilty of ringing the alarm bell, but sometimes that’s what you need to do, and unfortunately when it comes to the environment, there are so many alarm bells that need to be rung. I’ve been at this for a while now and at my age, I feel like we’re moving into a rebound stage of denial when it comes to the profound impact of climate change. I’m making a film right now in which I look at the problems around climate change not in terms of the science but the way we’re dealing with it as a topic and the solution, which is renewable energy, and why these things seem to be caught up in this pervasive indifference. It was my first time in front of the camera because I decided to educate myself and make a movie of my journey through this landscape. When you see young people who are optimistic and solutions-based in spite of what looms ahead, it makes you feel good.

I always felt that your father and Paul Newman used their power and influence in all the right ways, and it’s so great to see you continuing that legacy.

Well, it’s a funny thing. It happened over a long period of time, and it’s not really until you look back that you realize the direction your life has taken. Both of my parents had that impact on me. My mother was heavily into consumer advocacy and the solar lobby in the ’70s, and she continues to do stuff around women’s history. I just grew up in a very active household. Day to day I was more impacted by the things my parents cared about going on in the real world than anything else.

What are your plans for getting these films out into the world?

Our goal is to make “Resilience” and “Paper Tigers” as available as possible to people who will find them helpful and have a desire to see them. Because they are impact documentaries, they are not going to be picked up by Universal and seen on 2,000 screens. We have an ongoing relationship with a company called Tugg.com, which is basically a community screening distribution platform. You can license the film for an event online. We did this with “Paper Tigers,” and between the special event screenings and educational screenings, we had almost 4,000 screenings of the film in this country alone. We invest a lot of time forming alliances and relationships with stakeholders in the community. Just this morning here in Chicago, the Resiliency Institute had a two-day conference and asked me to bring my film to show it. In a situation like that, you have professionals from all walks of life being pulled in under a unifying topic, and when I go to screenings like this, I usually leave with a whole new set of contacts of people who would like to screen the film.

In a lot of ways, we are very much old-school in the sense that we have grassroots screenings and I live out of a suitcase going door to door to help fan the flames of awareness. But it actually works. If you asked me if I’d rather have 1,000 people at a screening or 100,000 impressions on Twitter or Facebook, I’d go with the 1,000 people because the sharing of content in the theater and the dialogue that happens afterward is so much more powerful. I remember the days when we finished a film and you handed it off and then you were just free to go about your life. It’s just not the nature of this kind of work. But I’ve learned so much and am so inspired when traveling around the country. The people I meet who have dedicated their lives to such important work is part of what makes this journey so great. One of our subjects in “Resilience,” [Clifford Beers Clinic site coordinator] Laura Lawrence, recently got a visit at work, out of the blue, from a young gentleman named David Wilkinson. He said to her, “I’m the Director of the White House Office of Social Innovation. The President and I watched ‘Resilience,’ and we were so struck by seeing the things we believe in represented onscreen. I just wanted to drop by and tell you how much I appreciate your work.” And that encounter changed her life. Things happen in mysterious ways.

“Resilience” screens at 8:15pm Saturday, November 5th, at Chicago’s Gene Siskel Film Center. Following the screening, James Redford will participate in a panel with The Honorable Clark Erickson, Chief Judge, Kankakee County; Dr. Emma Adam of Northwestern University; and Audrey Soglin, Executive Director of the Illinois Education Association; moderated by film critic Pamela Powell. For tickets, click here.

For more information, visit the official sites of “Resilience,” “Paper Tigers,” and The Redford Center.

Matt Fagerholm is the former Literary Editor at RogerEbert.com and is a member of the Chicago Film Critics Association.