Now streaming on:

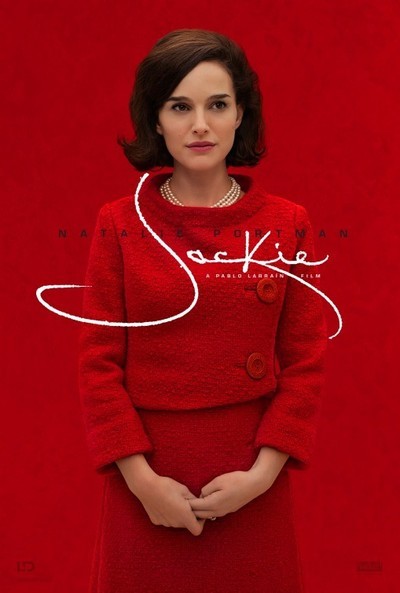

There are two movies in "Jackie," Pablo Larraín's film about Jackie Kennedy (Natalie Portman) immediately before, during and after the assassination of her husband, President John F. Kennedy. One of these movies is just OK. The other is exceptional. The first one keeps undermining the second.

Movie number one is a fictionalized biography in which a famous subject sits for a long interview, here with a magazine reporter played by Billy Crudup (unnamed but based on biographer Theodore H. White, who wrote “For President Kennedy: An Epilogue," a Life article that ran one week after President John F. Kennedy's assassination). This one is a movie where an important person contemplates his or her place in history and tries to control how they are perceived. It's fuzzy and overreaching and has been done better elsewhere.

The individual scenes in this "historical figure contemplates self" film are competently done and sometimes a good deal more than that, thanks to undertones of empathy and condescension in the dialogue. The reporter is often condescending to the former First Lady. Sometimes he even interrupts her when she's speaking or tries to put words in her mouth or dismiss her concerns, which shows how not-powerful even a very powerful woman can be when she's in a room with a man who's been told since birth that his words and actions are inherently more important than any woman's. This material in this second film connects to moments in the inevitable flashbacks to Jackie's heyday in Camelot and right after John F. Kennedy's murder. We see Jackie, often the lone woman in a room full of men, trying to assert herself and say what she wants and needs, only to be told (by White House staffers, military people, even her RFK) that it's impossible—because of security or protocol or precedent or simply because the men just mysteriously know better than her—and she should give up.

But the framing device is not ultimately necessary (few are, alas) because, whether the reporter and Jackie are talking about what's on the record or off the record, and whether what Jackie is saying is objectively true or merely self-serving, we have already seen everything both of them might have had to say illustrated, in a more immediate and often wrenching way, by the flashbacks.

The flashbacks constitute a second, far superior film, one that has the shock of revelation: we've seen this tight, crucial chapter of history re-enacted many times from all sorts of vantage points, but rarely in depth and mainly from the point-of-view of Jackie, who had to go through the gist of what everyone goes through when they lose a mate, only on the world's largest stage.

But whenever Larraín and his cast and crew build up a head of dramatic steam in the "past" (which feels far more "present" than the interview stuff), and keep building it up until it starts to feel like the raw material for an unwritten opera or an unmade psychological horror movie, "Jackie" fecklessly yanks us out of that emotional head-space, and returns us to the reporter and Jackie hashing over what it means.

The second movie in "Jackie" is new and often powerful, and it derives all of its newness and power from specifics. This "Jackie" is the story of a woman who suddenly, violently lost her husband, then had to figure out how to get through the next few days of her life without surrendering her sanity along with whatever power she once had. The mundane nature of this second movie is what makes it feel so eerily accurate. Details such as the specific bloodstains on Jackie's clothes and the bruise revealed on her shin as she takes her stockings off, the point-of-view shots of Jackie looking at all those men who have concluded they should decide her fate for her, the catch in Jackie's voice as she tries to tell her children that their father is dead without using the word "death," the way she goes into a depressive reverie and starts going through her clothes and trying on various dresses while listening to Jack's favorite album, the original cast recording of "Camelot": all of this feels achingly true. But Larraín pushes the "power" of it all too hard (often by ladling on Mica Levi's lyrical yet too often bombastic score). Even Portman's accent-driven performance, while ferociously committed, feels too much like a researched, considered, Marilyn Monroe-breathy impersonation, one that has been constructed from the outside in rather than incarnated from within. Rarely have I seen a more vivid example of artists getting in their own way and tripping themselves up.

A big part of the problem (for me, anyway) is that Larraín seems to want to make a statement, perhaps one of the ultimate statements, on the transformation of lived experience into myth. This film really doesn't have the intellectual chops to pull it off, never mind the question of whether that sort of movie is inherently more important and serious and worthy of critical superlatives than the simpler, more emotionally driven one about a widow coming to terms with the loss of her husband and her responsibilities to her children (both the biological ones and the symbolic ones, i.e. the American people).

Jackie as fantasy object upon whom hundreds of millions of less famous women can project their fears, goals and desires; Jackie as wife and mother, trying to keep it together during the worst few days of her life; Jackie as faithful spouse wounded by her handsome husband's infidelity; even Jackie as First Lady of the United States, looking out over a horrifically altered global landscape and asking what's next: all these Jackies are present in the hours and days preceding and following the murder. These various self-states are embedded in the way Jackie moves through rooms while the camera follows her, the way she looks at objects and people, and the way she struggles to compose herself and articulate her needs without deferring to whatever man she happens to be speaking with.

Jackie has to stand for herself but also for Jackie the historical figure, the myth, the oversimplification, the blank slate, the retrograde but at the same time revolutionary aspirational figure, and so on. We never feel as powerfully connected to this Jackie as we do to the one who suddenly has to move out of the house she's been living in for less than three years because her husband's brains were blown out in a motorcade. Meanwhile, the other characters are allowed to stand for one or two things only, always in relation to Jackie, and as a result, the film's supporting performances (particularly by Peter Saarsgaard as Robert Kennedy, who doesn't look or sound much like him, and who cares) feel a lot more fully imagined and realized. Actors always fail when they are asked to incarnate ideas, while they tend to do quite well with specifics like, "You are playing Robert, the brother of the murdered man, and the only person who understands your sister-in-law's pain."

The great movie that is "Jackie" keeps fighting to free itself from the clammy clutches of the could-have-been-better, knows-what-best-for-us movie. After a while the struggle becomes indistinguishable from the struggle depicted in the movie itself.

"Jackie" the drama (at times melodrama) knows what it is and what it wants to say. It trusts the audience to figure it all out and speaks to us via intuition, often taking considerable risks and making itself quite vulnerable. It is what would have been dismissed in another era as a "woman's movie"—i.e. a movie about the emotional experience of a woman—only to be reclaimed much later by historians and critics who struggle to get others to see that this kind of film is just as valid and worthy of scrutiny as the sort of movie where famous people sit for interviews about their legacy and spar about truth and fiction, performance and authenticity. (The character of Jackie is already starting to shape her own myth in the flashback material anyway; it's all there if you feel like looking for it, and as is the case throughout "Jackie," it's done with a lot more imagination than anything in the interview segments.) Ironic that Jackie's story here is mainly one of a woman trying to imagine her own experience on her own terms, only to be told by various parties, mainly male, that she's wrong, or that it's not enough.

Matt Zoller Seitz is the Editor at Large of RogerEbert.com, TV critic for New York Magazine and Vulture.com, and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in criticism.

99 minutes

Natalie Portman as Jacqueline Kennedy

Peter Sarsgaard as Robert Kennedy

Greta Gerwig as Pamela Turnure

Billy Crudup as The Journalist

John Hurt as The Priest

Max Casella as Jack Valenti

Sunnie Pelant as Caroline Kennedy

Beth Grant as Ladybird Johnson