If he’d only ever been a cinematographer, Jan de Bont would have had an impressive career. Working with Paul Verhoeven, Richard Donner and Ridley Scott, the Dutch cameraman helped lens some of the most memorable action films and thrillers of the 1980s and 1990s. (Two of the best movies of that era, “Die Hard” and “The Hunt for Red October” were shot by him.) But in the early ‘90s, shortly after filming “Basic Instinct,” he made the leap to directing, his debut the now-classic “Speed.”

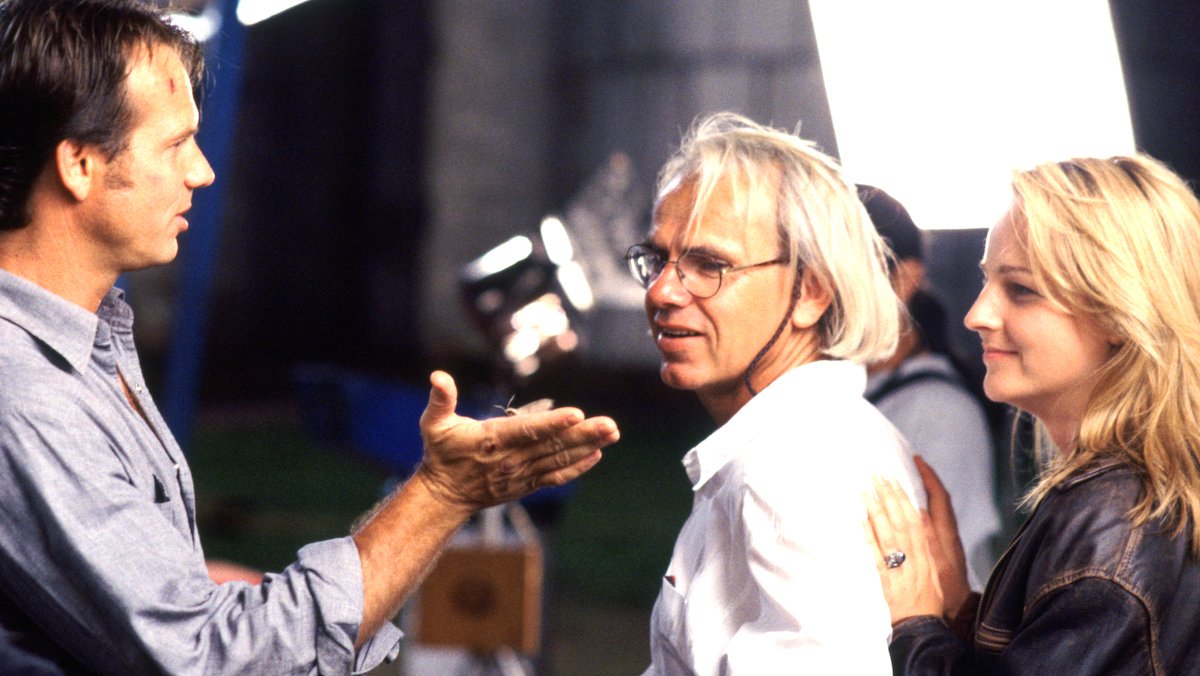

De Bont followed up that commercial and critical success with 1996’s “Twister,” a fun romp involving former storm chaser Bill (Bill Paxton) reluctantly tagging along with his soon-to-be-ex-wife (and fellow storm chaser) Jo (Helen Hunt) to track down a massive tornado. Bill needs Jo to sign the divorce papers so he can move on with his life—and marry his uptight fiancée Melissa (Jami Gertz)—but she’s too obsessed with this once-in-a-lifetime storm to focus on something so menial. (Plus, spoiler alert: Bill and Jo are still secretly in love with each other.) Amidst deadly winds, these two will rekindle their romance—depending on your perspective, “Twister” is the most expensive screwball romantic comedy ever.

“Twister,” which was the first theatrical film released on DVD, was a huge hit, and now it’s coming to 4K Ultra HD disc and digital. With “Twisters” about to land in theaters, it felt like a good time to talk to de Bont, now 80, about his film. But he also wanted to discuss the action-movie climate in which he came of age as a cinematographer. “In the ‘70s and ‘80s, those movies, everything was about those one-liners,” he says disparagingly over Zoom. “It drove me crazy because none of [those one-liners] were really funny—they were just a written sentence that quite often had nothing to do with the story, and it really annoyed the hell out of me. I worked on movies like that.”

Still, de Bont was committed to ensuring his own films were fun and funny—who could forget the infamous “Twister” scene involving a flying cow? I asked him about that, and also what it was like to work with a young Philip Seymour Hoffman, who played one of Jo’s colleagues. He also had thoughts about real-life storm chasers, modern blockbusters, and what he values in an action movie.

Rewatching “Twister,” I realized we don’t often have action movies these days that are also love stories. That’s true of this film but also “Speed.” Was building a romance into the narrative important to you as a director?

Anytime you can put regular human emotions in a movie, it makes people more aware that these are real characters. I like subplots that don’t always come to the foreground, but each time that little infusion makes the characters more real. I mean, [Jo] talks nonstop about science, but it’s nice to see her really have an argument about signing the [divorce] papers—that is such a simple thing, [but it’s] so great, so human. It doesn’t have to be a grand love story, like “Titanic”—[it can be] more regular.

When you made “Twister,” how concerned were you about the science being accurate? You didn’t stress out about that since you wanted to create a fun, escapist summer movie.

It is supposed to be fun, absolutely. But viewers have seen tornadoes on TV, so I felt that I have to make them look real. Otherwise, [it] would distract from the reality of the terror that they create—if you don't make them real, then you don’t believe the rest.

We worked a lot with not only storm chasers but Severe Storms Lab in Oklahoma, and they gave me so many movies and photographs of all different [storm] events. I ended up using a lot of that: If they happened for real, then they would be good for the movie. We had scientists on the set all the time—we had two storm chasers, we had two weather forecasters—for safety for the whole crew. It was nice talking to them—they became part of the crew. They knew all the lingo that exists about weather and storm-chasing.

I didn’t want to invent things—although, the cow is invented. Well, halfway-invented, because I saw a picture of [a] cow in a tree, which I thought was fake—and then they said, “No, it’s real.” I said, “Okay, we have to put it in the movie.” I started thinking, “Wow, wouldn’t it be great to see that cow flying through the air?” But I said, “Yeah, but just flying through the air, that’s kind of meaningless. If you see it from a car and you suddenly see [it] flying by, that’s much funnier because then there are people to react to it. Otherwise, if you see an abstract shot—‘Oh, cows flying’—that’s definitely not funny. You’re saying, ‘Oh, poor cow.’” Now, nobody says, “Poor cow.” They are saying, “Oh, funny cow.”

Back when “Twister” came out, storm chasers weren’t as big in the culture as they are now. What were the real-life storm chasers like that you met?

We got to understand their addiction to adrenaline and danger. But, also, those guys are weather nuts—they really photograph everything, film everything, and a lot of this stuff goes to the Severe Storms Lab. What they have fun doing, they want others to profit from it—I had no idea.

There are a lot more of them now. I think there are tour groups now for storm chasers, which is kind of silly to do as a tourist, but they do happen. But I think it’s also that, despite all the incredible improvements they have made in depicting tornadoes, they’re still deadly and they still come every year and destroy towns, farms, and trees. Nothing has really changed. So I think the chasers will be more visible, and I think that people [in tornado areas] will be more interested in weather than they ever were before because their life depends on it.

You didn’t grow up in a place with tornadoes. What was your first experience with a twister?

During the making, we [saw] some tornadoes, especially in pre-production, and they’re scary. They were actually more scary than I thought they would be. I always thought, “It looks so pretty, they move through the landscape…,” but when you get closer, they’re not so beautiful. And when you see the destruction, they’re really pretty bad.

You worked with the late Philip Seymour Hoffman before he was a household name, before he won an Oscar. His character Dusty is the film’s comic relief, a very different type of role than he would later play.

He was the last actor I cast. The casting director showed me some clips, but I was ready to focus on the movie [so] I really didn’t pay that much attention. [At the audition] I immediately liked how he sat in his chair when he entered the room, exactly like you see it [in the movie]. Really relaxed, laid back. [Jan de Bont imitates Hoffman’s character’s sitting style.] And I said, “That is Dusty.” The way he was dressed, the sloppy baggy pants and open shirt—I said, “Man, did he dress for the part?” I still don’t know, he never told me. It was so funny that we then ended up using that outfit for the movie—we just made duplicates of it.

He was an amazing character. He gave a lot of peace to the whole group. He’s calm, he was lighthearted. He could make a little joke about things that would smooth things out, but he also could go emotionally the other way. We started writing more scenes for him because there were not that many scenes in the movie [for him initially]. Basically, he helped to create his own role and increase it, making it a lot better.

This was your second film as a director after working as a cinematographer for years. I’m impressed by how confident you were in making blockbusters that were funny—these big movies had a light touch to them.

I absolutely knew that comedy, a lighter tone, was really important. It’s not the first time: When I was still working in Europe, in Germany, I was working on a TV series, which was basically the German version of “Monty Python’s Flying Circus.” I did a lot of episodes and I totally loved it.

People cannot underestimate what a few lighter moments can mean in a movie—it’s really, really, really key. And make it entertaining because, really, movies are entertainment. How can you make it entertaining and also be good at the same time—and exciting? The combination of that is harder to achieve—you have to work hard for that. But if it works, it works.

Your films were relatively small-scale. Nowadays, blockbusters have much bigger stakes than your films did: The planet is in danger, or maybe even the galaxy.

I wouldn’t want to make those movies. I wouldn’t be interested. By creating these lower expectations, you’re making it much more accessible for an audience. By keeping it on a smaller scale, I think an audience doesn’t have to work so hard to imagine a universe. If you make the scale so big, it loses your interest because you don’t want to invest all that time thinking about “How the hell does that happen? How does that world exist?” It’s just not worth it.

I want, honestly, to have two hours of a really good time. It's really to be excited, to be able to smile once in a while, to get emotions out. Don’t make it so big that [it] becomes ridiculous. You don’t want the whole city to come down [in “Twister”]—would that make a better movie? Absolutely not. It’s much better to see the effect on one farm, one family, than on the whole city. It becomes immediately abstract when you do it that big. I want it to be personal. I want it to be connectable. I don’t see me doing anything different.

Tim Grierson is the Senior U.S. Critic for Screen International.