Although most religions forbid it, human societies throughout history have accepted suicide as a reality. Sometimes, as in Japan, it was seen as a matter of personal honor. Usually it was seen as an act of despair, or a manifestation of insanity. It can also be seen as a rational act, and to assist someone in committing it can be seen as an act of mercy.

Although most religions forbid it, human societies throughout history have accepted suicide as a reality. Sometimes, as in Japan, it was seen as a matter of personal honor. Usually it was seen as an act of despair, or a manifestation of insanity. It can also be seen as a rational act, and to assist someone in committing it can be seen as an act of mercy.

I have never, even in my darkest hours, considered suicide. But with my troubles I have been fortunate; I've never had unbearable physical pain. In Barry Levinson's movie "You Don't Know Jack," Dr. Jack Kevorkian's best friend says his mother told him: "Imagine the worst toothache you've ever had. Now imagine that's how it feels in every bone of your body."

After Paul Schrader assured me Al Pacino's performance in the film was the best of the year, I rented it from Netflix, and after watching it I realized I didn't know Jack. He is depicted as tactless, cantankerous, argumentative, and brave. He was not a palatable poster child for assisted suicide, but perhaps it required a man with his single-minded zeal to bring the subject into discussion. He said he helped 130 patients kill themselves. Every time he was brought to trial in one of those cases of assistance, the jury acquitted him. He had kept video records of his interviews with the patients and the actual moments of their death, and jurors apparently agreed that he was providing medical help requested by a terminally ill person.

When he was finally found guilty, it was for second-degree murder. That came after he offered himself a test case for euthanasia. On a famous 60 Minutesprogram, he showed Mike Wallace a video in which he himself administered a fatal mixture of drugs. In all his previous cases, the patients had physically activated the death process. But what if a person lacks the physical ability to bring suffering to a halt?

In trying that last case, a prosecutor made a tactical call: He decided to drop charges of assisted suicide, in order to prevent any videos of the patient being seen by a jury. He chose to prosecute only on the narrow charge of murder in the second degree, for which Kevorkian himself had provided the documentary evidence. The doctor was sentenced to 10 to 25 years in prison, served eight and a half years, was paroled in 2007, and died on June 3, 2011.

Kevorkian's seems sometimes to have been carried away by excess zeal. This is from Wikipedia: "According to a report by the Detroit Free Press, 60% of the patients who committed suicide with Kevorkian's help were not terminally ill - at least 17 of them could have lived indefinitely - and in 13 cases, the patients had no complaints of pain. The report further asserted that Kevorkian's counseling was too brief (with at least 19 patients dying less than 24 hours after first meeting Kevorkian) and lacked a psychiatric exam in at least 19 cases, 5 of which involved people with histories of depression, though Kevorkian was sometimes alerted that the patient was unhappy for reasons other than their medical condition."

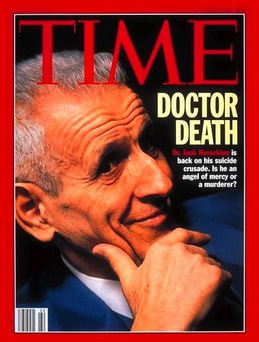

We must conclude that Kevorkian, called "Doctor Death" on the cover of Time magazine, sometimes acted too readily to bring about suicides which were a permanent solution to a temporary problem. He was a flawed men, carried away by belief in his cause. He brought attention, however, to assisted suicide, which I believe should certainly be allowed under strict medical and other guidelines. Polls showed that the majority of citizens in his state of Michigan supported him, and a poll taken after his death showed that 75% of Canadians approved of assisted suicide for terminal patients in pain.

So do I. The principal argument against it is religious: God gives life to men, who do not have the right to end it without his will. In a nation which separates church and state, this should not be a valid position. Why should it apply to someone who does not agree with it? If I am in agony, what difference do your beliefs about God make to me? What if I don't believe in God? What if I believe in a more merciful God, who gave me intelligence, free will and responsibility for my life? Why must I suffer because of your more narrow theology?

Several times a year we read of someone who assists a spouse, parent, child or partner to die. Sometimes this results in jail sentences. Much more often, I suspect, it happens silently. Doctors are forbidden to take overt action, but it is now accepted that passive action, "ending life support," is permitted. Many patients sign forms directing that their lives not be prolonged by extraordinary means. I have. When I am no longer capable of life as I understand it, I have no desire for my bodily functions to be artificially maintained. Indeed, once I have left the premises, I find the preservation of my corpse to be a distasteful thought, and have requested that it (not "I") be cremated. I am not my body. I am the mind that is directing my body to write these words. When my mind is no longer present, my body holds no interest for me.

"You Don't Know Jack," which was directed by Barry Levinson and played on HBO, is a provocative film. Schrader thought it was the best of the year, and told me that many directors of his generation believe cable television allows more freedom to make good movies than the traditional Hollywood system. He made a good point. Pacino won an Emmy for his performance, but was ineligible for an Academy Award. Here we have a film by the director of "Rain Man," "Wag the Dog" and "Bugsy," starring Pacino, Susan Sarandon, John Goodman, Danny Huston and (in a powerful role as Jack's sister) Brenda Vaccaro. With today's system of hammering teenagers into consuming "blockbusters," there seems to be no room for a film like this.

I finished the film with a positive opinion of Kevorkian, although to be sure it stacks the deck and leaves no doubt that his patients were suffering and consciously chose to end their lives. Pacino plays Kevorkian as an unbending man, plain-spoken, short on nuance. He defines himself as performing a required medical service for suffering people. The movie doesn't soften his edges or sentimentalize him. He is a little too proud of his "death machine" which pumps tranquilizers, sedatives and poisons into the system in that order. He's too blunt in interviews. Even those who love him are tested by his personality and his pattern of ignoring their advice.

He overcomes technical challenges in quick and direct ways. Lacking a place to carry out an assisted suicide, he puts a bed in the back of his VW van and performs the procedure on the isolated bank of a lake. Actual documentary footage suggests this vehicle, which he called his Suicide Machine, was a good deal shabbier than it appears in the film. Often he works in patients' homes, and in one harrowing case he needs two tries to asphyxiate a patient.

He lives in spartan quarters with his sister Margo (Vaccaro), who supports him wholeheartedly but is a good deal more flexible and reasonable than he is. She sees the big picture. He sees his Mission. In practical matters, his stalwart is his close friend Neal (Goodman), a medical supplies merchant who helps him construct devices, and rides shotgun on their missions of mercy. It was Neal whose mother was in such agony. There is also his friend Janet Good (Sarandon), a leader of the Michigan Hemlock Society.

These characters help Levinson and his screenwriter, Adam Mazer, flesh out the inflexible doctor. Kevorkian and his sister have a loud argument in a diner that is so emotional and heedless it equals in intensity anything Pacino has done. Pacino and Sarandon have a few quiet, tender scenes in which she tries to discover if he has ever really known love. It remains a good question. On her deathbed, they share a level of communication they were never able to achieve in life. No, they weren't in love. They shared an idealism.

Danny Huston plays Geoffery Fieger, the kind of attorney who advertises on TV but also a man who works for Kevorkian without any fee. That he later parlays his fame into a run for office is discouraging, but understandable. After Jack fires him he ends up with the lawyer who loses the case that sends him to jail. "Do you even have a law degree?" Fieger asks him.

Pacino and Levinson seem to have made a deliberate decision to keep Jack's rough edges. There is no attempt to make him heroic; we have to come to any such decision on our own. Pacino plays him as maddening and stubborn, in many cases his own worst enemy. Kevorkian comes across as warmer and more likable in his TV interviews than he does here. What cannot be doubted is his sincerity. He doesn't enjoy assisting people to die. He believes in it.

A recent HBO documentary, "How to Die in Oregon," was about death with dignity in that state that permits assisted suicide. It presented a softer and more idealized portrait of the procedure than "You Don't Know Jack." There was much more emphasis on the emotional and mental states of the patients, and less of Kevorkian's obsession with procedure and technique.

I recall two other powerful films. Denys Arcand's "The Barbarian Invasions" (2003) was about an intellectual joined in the process of death in a reunion with those who shared his life. There was a searing scene when his son, determined to alleviate his pain, boldly asked a narcotics detective how he could find heroin. Alejandro Amenábar's "The Sea Inside" (2004) starred Javier Bardem as a man paralyzed for 30 years, leading a campaign from his bed for his right to die.

I am in sympathy with these films. I believe we have free will, and the intelligence to use it. We should also have the freedom. When he was asked if he wasn't playing God, Dr. Jack replied with perfect logic: "Every doctor plays God." This is the simple truth. When doctor cut us open, stitch and mend, medicate us, drug us, radiate us and prolong our lives, they are playing God. In a more direct sense, if we choose to abuse tobacco, drugs, alcohol and wise nutrition, we are playing God. We have decided we should not live the lifespan our bodies were programmed for. And if we do not believe in God, we can hardly welcome someone else, or the law, playing God on our behalf. A penetrating and personal essay by Jeff Shannon on "How to Die in Oregon."

Roger Ebert was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.